It is election year in his country. The things he remembers—things he wants to forget—wake him up at the other end of the ocean. The writer, like everyone else, has been thinking of the election for long. But thoughts of the election are not what disturb his sleep. Instead, it is an image from a video recorded when he was a child. He cannot remember what year it was when he first saw the video. What he remembers is this: when he thinks of stark oppression, an image from that video is what comes to mind.

A man sitting beside another man, begging. The begging man’s suit is short-sleeved. He has no rings, jewelry, or wristwatch on. His expression is gaunt. He has a face full of fear, bleakness, and although what he says when he gets on his knees to continue pleading is inaudible, it is obvious how afraid he is for his own life.

The other man says nothing. His shiny attire glitters along with the furniture in the room. A golden cap sits with perfection on his head. Majesty. His silence intensifies the terror of the moment. Occasionally he swings his feet. His manner is iron—he is sure of his power over this begging man’s life and beyond. His dominance is entire. He says nothing all through the scene. Folds his arms for a while. Then he offers the begging man two handkerchiefs to wipe his tears.

A year passes. The powerful man has died, and with him—it seems at first—an irresponsible structure of power. His replacement, a man out of prison, sets up a panel to investigate atrocities against human rights in the country. The begging man from the video is invited before the panel. His alleged crime is planning a coup to overthrow the powerful man he was seen begging in the video. The video is alleged evidence—proof that he did plan a coup after all, and had gone to beg the powerful man after it failed.

The proceedings are televised. The begging man knows the worst is behind him—he has outlived the dastardly, powerful man; the one that cannot be reasoned with. He can maneuver his way out of the clutches of these civilians, people who, just two years back, wouldn’t have dared to lace his shoes. When he appears before the panel, his agbada is overflowing. His gold-rimmed glasses have returned. A large golden ring. Golden bracelets and a glimmering necklace around his neck. He evades questions. Bobs his head from side to side. His days of begging are over.

The new leader—who isn’t really new since he too was Head of State in another era—has also been invited to stand before the panel. He is, allegedly, responsible for burning the house of the country’s greatest ever musician and for throwing the musician’s mother—herself one of the country’s most eminent people—out the window of a two-story building.

The new leader stands before the panel with obvious contempt. His tongue is in his cheeks, literally. Bobs his head from side to side as he answers. Bats his lashes. Shuffles his feet. Instructs the lawyer questioning him to show him respect. Untouchable men recognize their untouchability.

The name of the station broadcasting the event is the Nigerian Television Authority. Authority. In this country what you see, what you’re shown, cannot be questioned…

—

It is 2.33am as he writes. On his table is a half-open book. A number of pencils and pens. Sticky notes. A mug. In the mug, a small Nigerian flag. He keeps the flag, not out of patriotism, but as a reminder of his own trans-Atlantic shift. Also, on the table, four images he has been thinking about.

In the first photograph a man stands on a bus with arms raised. He is wearing a white, flowing attire. Dark shades. Below him, around him, a huge crowd raising their hands towards him. On the far left of the photograph is a poster with a smiling man. The face in the poster is the same face now standing on the bus. The photograph, from 2014, is a scene from an election campaign in a south-western state of the country and, the man on the bus is a gubernatorial aspirant.

Another photograph from 2014. Same south-western state, similar central figure. A man—major opponent of the man on the bus—his head out from the roof of a car, poses with two cobs of corn. He is wearing an attire with yellow and blue patterns. He is also wearing dark shades. A fine cap folded neatly on his head. His wristwatch and rings glow in the photograph. Behind him, a series of SUVs with sirens indicate that he is part of a convoy. Light and glitter bounce off the vehicles.

The writer pauses to consider both photographs. The first seems entirely organic: a popular man standing on a bus, hailed by an endless mass of followers. Yet, closer looking suggests otherwise. Where is the photographer standing? The photographer has to be at some higher height than the crowd for the photograph to make sense, for it to be possible. Also, the street where the scene happens seems too perfect: its downward slope is just enough to show the thickness of the crowd, the houses around, the houses behind; the street could even be a summary of the town—anyone looking at the photograph could say the whole town is here and they would be right. Again, the poster to the left of the photograph. Somehow the photographer has managed to sneak it into the image. The writer thinks, why is the man on the bus wearing dark shades and not the same glasses in the poster which he might actually require to see properly? Or perhaps the right question is, what is the man on the bus looking at, what doeshe want to see? The writer considers the man on the bus again and thinks to himself, this man isn’t looking at the crowd below him. Instead the man on the bus is looking directly at the photographer, into the camera. He isn’t raising his hands to the crowd, he is raising his hands to the photographer. The whole gesture is a ruse, a pose, a signal to the photographer to say: it is time, photograph me.

The writer sees how the second image lacks tact unlike the first. He remembers the time when politicians publicly eating corn became a thing—a governor from another state had been praised for “living like the people”, for “stomach infrastructure”, for stopping by the roadside to roast plantain with market women and these acts were said to have helped in getting him elected. The man in the second image—the corn man—holds the cobs of corn out in readiness for the photograph. There is a slight look of impatience on his face. The photograph is a necessity, a compulsory act. The writer knows that a few minutes after the image is made the corn man will get back in his air-conditioned SUV. He will instruct his driver to turn up the music, and the convoy will resume its motion, sirens blaring as it leaves.

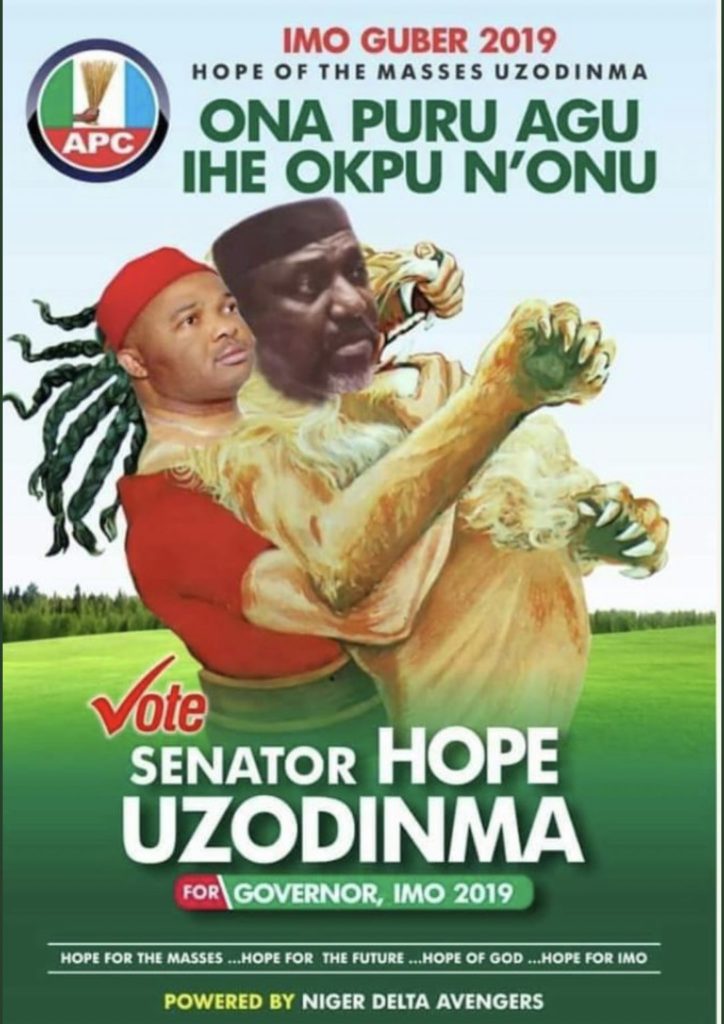

The other two images are more recent and are targeted at the year’s election. One of them is a campaign poster. At first it is unclear what is happening in the poster. A mixture of photographs, illustrations, and graphic design. At once, for the writer, the poster seems familiar. He recognizes the illustration. It is from a book many children in his country grew up with—My Book of Bible Stories, and the scene depicts Samson’s fight with a lion. In the bible version Samson had killed a lion and found honey in its corpse. For the poster the writer wonders what is the message of the modified illustration. He studies the poster for clues. The heads of Samson and the lion have been replaced with the heads of two male figures. The head that replaces Samson’s belongs to a senator contesting to become the governor of a south-eastern state. The other—the head that replaces the lion’s—belongs to the current governor of the same state. At the top of the poster is a large inscription in Igbo, equaled only in size by the senator’s name.

ONA PURU AGU IHE OKPU NONU.

The senator considers himself a type of Samson, the anointed one, the one strong enough to snatch what the incumbent governor—the lion—has kept in his mouth. There is no text on the poster indicating the senator’s manifesto, his plan, his agenda if he does become governor. Instead, there is a play on words with the senator’s name plastered all over the poster: Hope for the Masses. Hope for the Future. Hope of God. Hope for Imo. At the bottom of the poster, an inscription the writer finds amusing: POWERED BY NIGER DELTA AVENGERS.

In the final photograph the country’s president is dressed in a glowing red attire with leopard patterns. The attire has large, bronze, ornamented buttons. Around his neck, an elaborate ceramic bead. In his right hand, a horn. He is wearing a red cap and a polished smile. The president, a northerner, is dressed in an attire for south-eastern chiefs. The last time he dressed like this for a photograph was four years before, during the campaign for his current tenure.

—

It is now 6.33am and the writer is tired. Still, proper historicizing demands resilience. It also demands a multiplicity of looking; the eye that looks only once cannot be trusted. He considers the four images again and thinks about the video. All contain powerful men. But the powerful man in the video is different from the others: he is a culmination of an era that began long before him, an era where the powerful posited themselves visibly as merchants of violence. Coups. Counter-coups. Letter bombs. Soldiers on the streets, whipping people in line.

When the writer remembers the recent display of military might in the east to shut up protesters and the murder of members of a religious sect up north, he realizes how erroneous it is to believe the era of tyranny has ended. Tyranny never left the country; it has only put on a mask, a new attire. Its era did not end, it simply morphed. In place of violence the powerful now associate themselves, visibly, with representation—tyranny is hard to recognize when it looks like you.

Yet the writer is not satisfied with his theory of representation. Truly the four images, in some sense, are attempts to patronize the masses. But the images seem to contain something else. He decides to start again from the beginning. He goes back to the video of the first leader from 1999, standing before the human rights panel. The body language, the head bobbing, the shifting from side to side. A kind of restlessness associated with stage performances. The country has always been a stage, an elaborate drama. Or maybe, the writer thinks, the word is not drama. Drama is too general; it suggests something simple, petty, flimsy. The word he is searching for is theatricality. Theatricality is more complex, robust enough to hold the fullness of what the four photographs suggest. A man on a bus, a corn man, a man and a lion, a man in a disguise—all masterful machinations of theater, designed to hold any onlooker spell-bound. To what end? Definitely not entertainment, although the photographs are indeed entertaining. The relationship between the audience in a theater and the actors on stage transcends entertainment. It is one of kinship, of identity. Actors rely on a certain kinship with the audience to perform a comedy for instance. They know what the audience will laugh at. Therefore, the joke an audience finds funny says more about the audience than the comedian. In the same way, the writer realizes, how the leaders of a people decide to be photographed says more about the people than the leaders themselves.